Maharashtra Kidney Racket Case: A Systemic Analysis of Organ Trafficking Networks, Regulatory Failure, and Socio-Economic Exploitation (2000–2025)

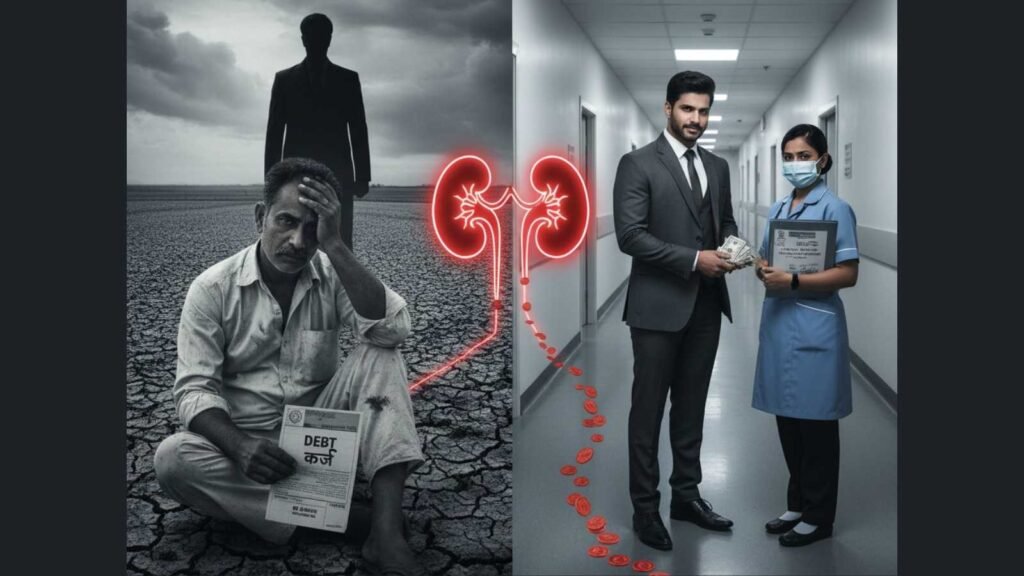

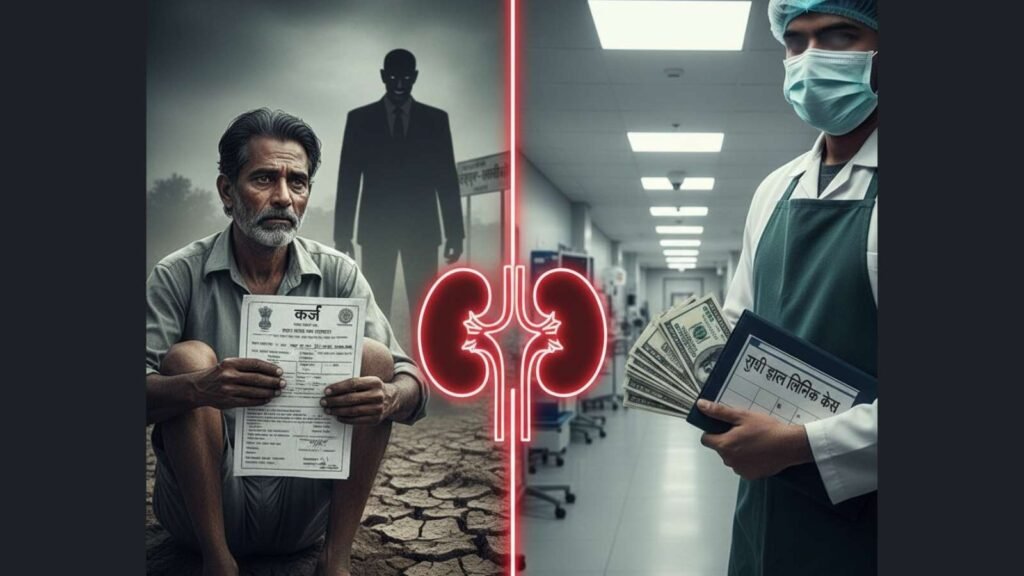

1. Introduction: The Political Economy of the “Red Market”

The state of Maharashtra, serving as one of India’s premier hubs for advanced tertiary healthcare and medical tourism, has simultaneously emerged as a critical node in the global illicit trade of human organs. This report offers an exhaustive, forensic examination of the kidney trafficking rackets that have plagued the state over the last two and a half decades. From the early, individualized malpractices of rogue surgeons in the early 2000s to the highly sophisticated, corporate-backed syndicates of the mid-2010s, and finally, the alarming transnational debt-bondage trafficking rings exposed in 2025, the evolution of the “Red Market” in Maharashtra reflects a catastrophic failure of regulatory oversight and a deep-seated socio-economic crisis.1

The trade in human kidneys in India is not merely a medical crime; it is a symptom of profound structural inequality. It thrives in the chasm between the desperate demand for organs—where approximately 200,000 patients develop end-stage kidney disease annually against a supply of only 13,000 transplants—and the desperate poverty of the donor population.5 In Maharashtra, this trade has evolved through distinct phases. Initially characterized by the exploitation of urban poor and slum dwellers, recent investigations in 2024–2025 have uncovered a sinister shift toward the agrarian heartland of Vidarbha, where debt-ridden farmers are coerced by illegal moneylenders into selling organs to service usurious loans, with trafficking routes now extending to Southeast Asia, specifically Cambodia.2

This analysis dissects the legal architecture of the Transplantation of Human Organs Act (THOA), the pivotal scandals at L.H. Hiranandani Hospital and Ruby Hall Clinic, the administrative rot exemplified by the case of Dr. Ajay Taware, and the emerging international dimensions of the trade. It synthesizes data from police charge sheets, court orders, medical council proceedings, and legislative debates to provide a definitive record of the state’s battle against the commodification of human life.

1.1 The Legal Framework and Its Loophole: THOA 1994 to 2014

To understand the persistence of these rackets, one must first critique the regulatory environment. The Transplantation of Human Organs Act (THOA), 1994, enacted to criminalize commercial dealings in organs, established a framework based on “altruism.” However, the Act, even after its 2011 and 2014 amendments, contains structural vulnerabilities that traffickers have weaponized.3

The Act categorizes living donors into two primary groups:

- Near Relatives: Defined as parents, children, siblings, spouses, grandparents, and grandchildren. These donors require minimal clearance.

- Other Than Near Relatives: Individuals who can donate only for reasons of “affection and attachment” towards the recipient or for a special reason, provided there is no financial transaction.

The “Other Than Near Relative” clause is the single largest entry point for corruption. It necessitates an Authorization Committee (AC)—a statutory body comprising medical and government officials—to interview the donor and recipient, video-graph the proceedings, and certify that the donation is altruistic.3 In Maharashtra, these committees exist at the hospital level (for centers conducting over 25 transplants annually) and at the state/regional level (Regional Authorization Committees or RACs).10

The fundamental failure observed across all major rackets in Maharashtra is the compromise of the Authorization Committee. Whether through negligence, lack of forensic capability to detect forged documents, or active collusion (as alleged in the Dr. Ajay Taware case), the AC has repeatedly failed to distinguish between genuine altruism and coached performance, allowing paid donors to pass as “family friends” or “servants” with deep emotional ties to the recipient.3

2. The Hiranandani Hospital Kidney Racket (2016): The Corporate Nexus

The exposure of the kidney racket at the prestigious L.H. Hiranandani Hospital in Powai, Mumbai, in July 2016, marked a watershed moment in the history of medical crime in India. It shattered the public perception that organ trafficking was the domain of fly-by-night clinics, implicating instead the C-suite executives and top transplant surgeons of a super-specialty corporate hospital.4

2.1 The Bust: July 14, 2016

The racket was dismantled not by regulatory vigilance but by the intervention of civil society. On July 14, 2016, a team comprising social worker Mahesh Tanna, members of a trade union, and political activists tipped off the Powai police about a suspicious transplant scheduled at Hiranandani Hospital. The operation was intercepted midway. The intended recipient was Brijkishore Jaiswal (48), a textile businessman from Surat, and the donor was Shobha Thakur (42), a domestic worker from Gujarat.4

The Deception Mechanism:

The investigation revealed a classic “fake family” model. Documents submitted to the hospital identified Shobha Thakur as “Rekha,” the wife of Brijkishore Jaiswal. The paperwork was extensive and forged, including:

- A fabricated marriage certificate purporting to show a long-standing union.

- Forged ration cards and Aadhar cards to establish a common address.

- Affidavits declaring the relationship.

In reality, Jaiswal’s actual wife was nowhere in the picture. Thakur had been recruited by a network of agents who exploited her financial destitution. She was promised approximately ₹2–3 lakhs for her kidney, while Jaiswal was charged a significantly higher sum, with the difference siphoned off by the agent network.14

2.2 The Syndicate Structure and the Whistleblower

The operation was orchestrated by Bhijendra Bisen (alias Sandeep), a notorious agent with a history of organ trafficking arrests dating back to 2007. Bisen’s network included multiple layers of middlemen, including Bharatbhushan Sharma and Iqbal Khan, who managed the logistics of procuring donors, housing them, and coaching them for the Authorization Committee interviews.14

The Tragic Role of Sundar Singh:

The case was blown open by the testimony of Sundar Singh, a 23-year-old migrant laborer. Singh was not merely a witness but a victim-turned-operative. In March 2016, months before the bust, Singh had been lured into selling his own kidney at Hiranandani Hospital. He was trafficked from Delhi, housed in Mumbai, and made to pose as the brother of a female recipient.

- The Betrayal: Singh was promised a substantial sum but was defrauded by the agents after the surgery. In a cruel twist, the agents offered him a “job” to recoup his losses: he was to act as a handler for future donors, managing their accommodation and food while they awaited surgery.

- The Revelation: It was Singh who provided the critical intelligence regarding the Jaiswal-Thakur transplant to social workers, driven by a desire for retribution against the syndicate that harvested his organ and stole his compensation.

- The Aftermath: Singh’s story ended in tragedy. In January 2019, his decomposed body was found hanging from a ceiling fan in his residence in Diva, Mumbai. While police initially ruled it a suicide driven by financial stress and lack of protection, his death raised disturbing questions about the safety of whistleblowers in high-stakes criminal cases involving powerful medical lobbies.16

2.3 Investigating Institutional Complicity: The 1,000-Page Charge Sheet

The Powai police investigation, led by DCP Vinayak Deshmukh, culminated in a massive 1,000-page charge sheet filed in October 2016. This document was historic as it charged the hospital’s top administrative and medical leadership under the Indian Penal Code (IPC) and the Transplantation of Human Organs Act (THOA).14

The Accused Medical Hierarchy:

- Dr. Sujit Chatterjee (CEO): The police alleged that as the head of the institution, Dr. Chatterjee was liable for the systemic failure to verify documents. The charge sheet cited a report by the Directorate of Health Services (DHS) which pointed to “negligence” and the ignoring of suspicious patterns in transplant applications. It was revealed that the DHS had previously flagged the hospital’s transplant coordinator, Nilesh Kamble, for suspicious activities, a warning the administration allegedly ignored.13

- Dr. Anurag Naik (Medical Director): Charged alongside the CEO for administrative lapses and failure to oversee the Authorization Committee’s functioning.13

- The Transplant Team: Three senior doctors—Dr. Mukesh Shete (Nephrologist), Dr. Mukesh Shah (Urologist), and Dr. Prakash Shetty (Nephrologist)—were arrested. The police contention was that these doctors, who had close interactions with the patients, should have detected the lack of genuine familial rapport between the donor and recipient. The doctors’ defense argued that their role was strictly clinical and that verification was the duty of the state and the hospital’s administrative wing.13

- Dr. Suwin Shetty (Pathologist) & Dr. Veena Sewlikar (Surgeon): These doctors approached the Dindoshi Sessions Court for anticipatory bail. The court rejected their pleas in August 2016, observing the “serious nature” of the crime and the necessity of custodial interrogation to uncover the depth of the conspiracy. The court noted that as members of the hospital’s internal scrutiny committee, they had failed to detect obvious forgeries in the documents.20

2.4 Legal Defense and Judicial Observations

The legal battle following the arrests brought to the fore the tension between medical practice and policing duties.

- The Defense Argument: Represented by prominent criminal lawyers like Aabad Ponda and Brian D’Lima, the doctors argued that the THOA does not empower or require doctors to act as forensic experts or private detectives. They contended that if the Authorization Committee (which includes government nominees) clears a file, the surgeon is legally bound to proceed. They emphasized that they were full-time clinicians with no financial incentive to participate in the racket, as their fees were standard.19

- The Prosecution’s Stance: The police and public prosecutor argued that the “willful blindness” of the doctors amounted to criminal conspiracy. They highlighted that the sheer volume of transplants facilitated by specific agents like Bisen should have raised red flags. The recovery of ₹8 lakhs from the home of the transplant coordinator, Nilesh Kamble, was presented as evidence of a cash-for-approval kickback system embedded within the hospital.13

Outcome:

The five doctors, including CEO Dr. Chatterjee, were eventually granted bail of ₹30,000 each in August 2016, subject to stringent conditions including surrendering their passports and reporting to the police station. However, the reputational damage was permanent. In 2024, after 22 years of service, Dr. Sujit Chatterjee stepped down as CEO, a move widely interpreted as the closing chapter of the scandal’s administrative fallout.19 The hospital’s transplant license was suspended temporarily, and an external audit by Ernst & Young was commissioned to review all past cases, though the full findings of this audit remain internal.16

3. The Ruby Hall Clinic Racket (2022): The Swap Transplant Fraud

While the Hiranandani case focused on “fake families,” the racket unearthed at Pune’s Ruby Hall Clinic in 2022 exposed the manipulation of the “Swap Transplant” provision. This case is pivotal because it implicated the Regional Authorization Committee (RAC) itself, moving the locus of criminality from the hospital corridor to the regulator’s office.23

3.1 The Mechanism of Fraud: The “Swap” Loophole

The Swap Transplant provision in the THOA allows two pairs of donor-recipients, who are incompatible with each other (e.g., due to blood group mismatch), to exchange organs. Pair A’s donor gives to Pair B’s recipient, and vice versa. This requires four surgeries and rigorous verification of two separate families.8

The Case of March 2022:

The fraud at Ruby Hall involved a woman from Kolhapur who was recruited to pose as the wife of a patient named Amit Salunkhe.

- The Proposition: Agents promised the woman ₹15 lakhs to impersonate “Sujata Salunkhe” (Amit’s real wife).

- The Swap: As “Sujata,” she was to donate her kidney to a third-party recipient, Sonal Kadam. In exchange, Sonal Kadam’s relative would donate a kidney to Amit Salunkhe. This complex arrangement effectively laundered the illegal commercial transaction within a legal medical framework.

- The Unraveling: The surgery took place on March 24, 2022. However, the woman was not paid the promised ₹15 lakhs. Feeling cheated, she revealed her true identity to the hospital staff and subsequently to the police on March 29, 2022, four days post-surgery. This admission collapsed the entire house of cards.24

3.2 The Administrative Response and License Suspension

The revelation triggered a swift but contested response from the state apparatus.

- Hospital’s Defense: The Managing Trustee of Ruby Hall Clinic, Dr. Purvez Grant, and CEO Bomi Bhote claimed the hospital was the victim of fraud. They argued that they had relied on the police verification report and the approval of the Regional Authorization Committee (RAC) at Sassoon General Hospital. They pointed out that they were the ones who alerted the police once the woman confessed.23

- State Action: The Directorate of Health Services (DHS) was unconvinced. In April 2022, the DHS suspended Ruby Hall Clinic’s registration for organ transplantation. The suspension covered both live and cadaveric transplants, a move that paralyzed the region’s transplant program. The DHS inquiry concluded that the hospital’s internal scrutiny committee had failed to verify basic documents like Aadhar cards and marriage certificates, which were found to be forged.28

- Legal Battles & Reinstatement: The hospital challenged the suspension in the Bombay High Court. In September 2023, after a year of legal wrangling and a “routine inspection” by a 22-member state health team, the license was renewed. This renewal, despite the gravity of the allegations, highlighted the “too big to fail” status of major medical institutions in the state’s healthcare ecosystem.30

4. The Fall of Dr. Ajay Taware: Institutionalizing Corruption

The investigation into the Ruby Hall racket took a sensational turn when it pointed upwards to the regulator. The focus shifted to Dr. Ajay Taware, the Medical Superintendent of the government-run Sassoon General Hospital and the Chairman of the Regional Authorization Committee (RAC).11

4.1 The Regulatory Capture

Dr. Taware, as the head of the RAC, held the ultimate power to approve or reject transplant applications for the entire Pune region. The police investigation revealed that the approval for the Ruby Hall swap transplant was not merely an error of judgment but an act of criminal conspiracy.

- The Allegations: The Pune Crime Branch found evidence that Dr. Taware and his committee members had approved the transplant despite glaring discrepancies in the documents submitted by the “fake wife.” The police alleged that Taware was part of a syndicate that facilitated approvals for a fee, effectively turning the RAC into a clearinghouse for illegal transplants.11

- Modus Operandi: Taware allegedly coached agents on how to structure applications to bypass scrutiny. The inquiry committee headed by a retired High Court judge found that Taware had approved procedures based on forged documents that were visibly fraudulent even to the naked eye.11

4.2 The Porsche Case Connection (2024–2025)

Dr. Taware’s criminal profile expanded dramatically in May 2024. Following the infamous Pune Porsche crash—where a drunk minor killed two engineers—Dr. Taware was arrested for orchestrating the swapping of the minor’s blood samples with those of his mother to ensure a negative alcohol test.

- The Dual Arrest: While Taware was in judicial custody at Yerwada Central Jail for the Porsche case, the Pune Crime Branch formally arrested him again in May 2025 for the Ruby Hall kidney racket. This “double booking” cemented his status as the central figure in Pune’s medical corruption.26

- Political Patronage: The investigation exposed deep political links. It was revealed that Taware had been reinstated as Medical Superintendent in December 2023—despite the pending inquiry into the kidney racket—following a specific recommendation letter from NCP MLA Sunil Tingre to the Medical Education Minister Hasan Mushrif. This revelation forced the resignation of the Sassoon Hospital Dean, Dr. Vinayak Kale, who claimed he was pressured by the minister to reinstate Taware.33

4.3 Legal Status and Bail (2025)

In August 2025, the court of JMFC A.A. Pandey granted bail to Dr. Taware in the kidney racket case. The magistrate’s reasoning was legally technical: “Seriousness of an offence cannot be a ground to reject bail.” The court noted that the investigation was complete, the charge sheet was filed, and Taware’s role was limited to documentary verification. However, Taware remained in jail due to the more serious charges in the Porsche blood-swap case (forgery, destruction of evidence).35 Concurrently, the Maharashtra Medical Council (MMC) suspended his registration, barring him from practice.36

5. The Agrarian Crisis and Transnational Trafficking: The Chandrapur-Cambodia Axis (2025)

By late 2024 and throughout 2025, the locus of the kidney trade shifted from the urban centers of Mumbai and Pune to the distressed agrarian districts of Vidarbha, revealing a terrifying new trend: Debt-Bondage Organ Trafficking linked to international crime syndicates.2

5.1 The Victim: Roshan Kude and the Debt Trap

The case of Roshan Sadashiv Kude, a farmer from Minthur village in Chandrapur district, personifies the desperation of the Indian farmer.

- The Debt Spiral: In 2021, Kude borrowed a relatively small sum of ₹1 lakh from private moneylenders to support his failing farm and dairy business. The moneylenders charged an extortionate interest rate of 40% per month. By 2024, the compounded debt had ballooned to a staggering ₹74 lakhs.6

- Coercion and Torture: Kude filed a police complaint detailing how the moneylenders—identified as the gangs of Kishor Bawankule, Laxman Urkude, and others—kidnapped him, confined him, and physically tortured him. They presented a single option for release: the sale of his kidney.6

5.2 The Transnational Logistics: Kolkata to Cambodia

Unlike previous rackets where surgeries were performed in domestic hospitals, Kude’s exploitation involved an international supply chain.

- The Route: Kude was first transported to Kolkata, which has emerged as a key transit hub for donors being trafficked to Southeast Asia. There, he underwent preliminary compatibility tests.7

- The Destination: He was then flown to Cambodia. While the specific hospital in Cambodia remains unnamed in public police files, reports link this to the broader network of “scam compounds” and illegal medical facilities operating in the Mekong region (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar).2

- The Payout: The surgery took place in October 2024. Kude was promised a life-changing sum but received only ₹8 lakhs—a fraction of his ₹74 lakh debt. He returned to India physically mutilated and still in debt, prompting him to approach the police.6

5.3 SIT Investigation and Broader Implications

In December 2025, Maharashtra Deputy Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis ordered the formation of a Special Investigation Team (SIT) to probe this racket. The SIT, led by Additional Superintendent of Police Ishwar Katkade, arrested six moneylenders. The investigation is currently probing links between these rural moneylenders and international organ trafficking cartels that likely supply organs to wealthy buyers in the Middle East and the West who travel to Southeast Asia for “transplant tourism”.2

This shift to Cambodia is significant. It bypasses Indian regulatory oversight entirely. Indian police face severe jurisdictional challenges; Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties (MLATs) are slow, and the crime occurs in jurisdictions with weak rule of law. This represents the “offshoring” of the Indian kidney trade.39

6. Socio-Economic Analysis of the Donor Pool

A comprehensive analysis of the donor profiles across these rackets reveals the stark socio-economic determinants of the trade.

6.1 Gender Disparities: The Feminization of Donation

Data from 2024 indicates a profound gender imbalance in Indian organ donation. Approximately 79% of living kidney donors are women, while 81% of recipients are men.41

- Societal Conditioning: Women (wives and mothers) are culturally conditioned to be “altruistic” donors to save the male breadwinner. In the illegal trade, this vulnerability is exploited. Traffickers prefer female donors because they are perceived as more compliant and less likely to demand higher payments or report the crime.9

- The “Fake Wife” Trope: The Hiranandani and Ruby Hall cases both utilized women posing as wives. This is not coincidental; Authorization Committees are culturally predisposed to accept a wife donating to a husband as a natural, non-commercial act, making it the perfect cover for traffickers.14

6.2 Economic Drivers: From Urban Slums to Rural Farms

- Urban Donors (2000s–2010s): Donors like Sundar Singh were typically urban migrants, unemployed, or casual laborers living in slums. The motive was often immediate cash for survival or debt repayment.18

- Rural Donors (2020s): The Chandrapur case highlights a shift to the agrarian sector. The collapse of the rural economy and the dominance of predatory informal credit markets (moneylenders) have turned farmers’ bodies into collateral. The “biological citizenship” of the poor is defined by their ability to strip their biology for assets.6

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Maharashtra Kidney Rackets

| Feature | Hiranandani Racket (2016) | Ruby Hall Clinic Racket (2022) | Chandrapur Racket (2025) |

| Primary Location | Mumbai (Powai) | Pune | Vidarbha (Victim) / Cambodia (Surgery) |

| Modus Operandi | “Fake Family” (Wife/Brother) using forged documents. | “Swap Transplant” Fraud; impersonating a spouse in a swap pair. | Debt Coercion by Moneylenders; International Trafficking. |

| Key Medical Figures | CEO Dr. Sujit Chatterjee, Dr. Mukesh Shete | Dr. Ajay Taware (RAC Head), Dr. Purvez Grant | Unknown Cambodian Doctors / Kolkata Agents |

| Whistleblower | Sundar Singh (Donor turned Agent) | Female Donor (Fraud Victim) | Roshan Kude (Farmer/Victim) |

| Regulatory Action | CEO Arrested; License Suspended; Audit. | RAC Head Arrested; License Suspended & Renewed. | SIT Probe; Moneylenders Arrested. |

| Key Insight | Corporate negligence & failure of internal checks. | Corruption of the Regulatory Authority (RAC). | Intersection of agrarian crisis & transnational crime. |

7. Policy Responses and Future Outlook

The state’s response to these crises has been reactive, characterized by cycles of scandal, crackdown, and eventual return to status quo.

7.1 Tightening the Net: New Guidelines (2023–2025)

In response to the recurring scandals, the DMER and the Union Health Ministry issued new guidelines in 2023 and 2024.

- Foreign Nationals: A June 2024 circular mandated stricter verification for foreign nationals. Form 14C (Embassy Certificate) must be verified directly with the embassy, and the “near relative” status must be established with greater rigor. This was a direct response to the “internationalization” of the trade.10

- Domicile Verification: New norms require clearer proof of domicile to prevent “transplant tourism” between states, where donors from one state (e.g., UP or West Bengal) are brought to Maharashtra for surgery.10

7.2 The Failure of the “Affidavit” System

The core vulnerability remains the reliance on documentary evidence. As noted in the Hiranandani case defense, doctors are not forensic experts. A notarized affidavit or a laminated Aadhar card is easily forged. Until the Authorization Committee process is integrated with biometric verification (linking strictly to the UIDAI database) and potentially includes DNA testing for all alleged relatives (a proposal often debated but stalled due to cost and urgency), the “fake relative” loophole will remain open.3

7.3 The Way Forward

The trajectory of the kidney racket in Maharashtra—from the individual malpractice of Suresh Trivedi to the international syndicate of the Chandrapur case—demonstrates that the trade is highly adaptive. It moves to where the regulation is weakest.

- Strengthening Deceased Donation: The only long-term solution to the demand-supply gap is a robust deceased donor program. While Maharashtra has made strides (crossing 1,000 deceased donations nationally in 2023), it is still insufficient to crush the black market.9

- Regulating the Private Sector: The impunity of large corporate hospitals must be addressed. Fines and temporary suspensions have proven to be ineffective deterrents. There is a need for criminal liability provisions that pierce the corporate veil, holding management boards accountable for the clinical practices on their premises.

- Addressing Agrarian Distress: The Chandrapur case proves that medical policy cannot be divorced from economic policy. As long as farmers are trapped in debt bondage with no formal recourse, their organs will remain a currency of last resort.

In conclusion, the Maharashtra kidney rackets are a dark mirror to the state’s development. They reflect the commodification of the human body in an era of extreme inequality, where the advanced medical capabilities of Mumbai and Pune are fed by the despair of the hinterlands. Without a systemic overhaul that addresses both the medical regulation and the socio-economic drivers, the “Red Market” will continue to thrive in the shadows.