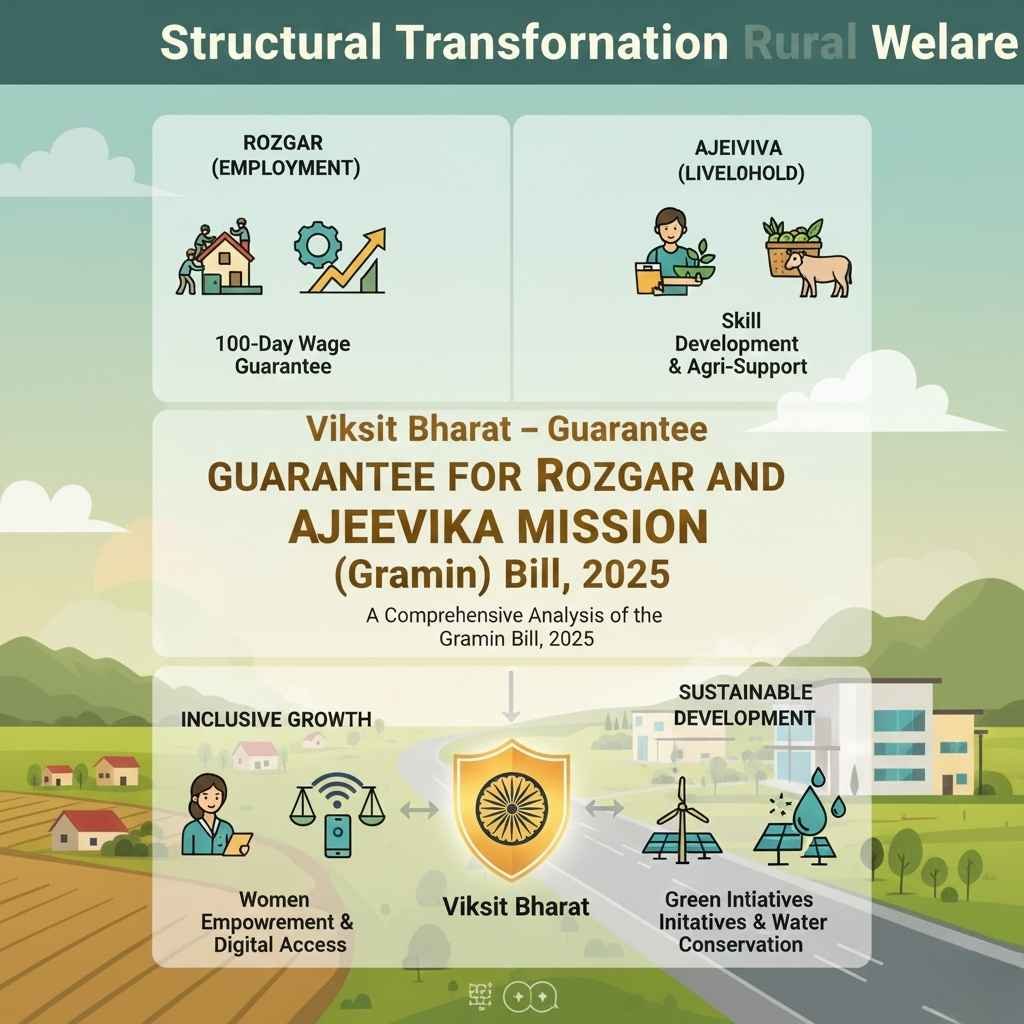

Structural Transformation of Rural Welfare: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Viksit Bharat – Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) Bill, 2025

1. Executive Summary

The introduction and subsequent passage of the Viksit Bharat – Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) Bill, 2025 (henceforth VB-G RAM G) represents a seminal inflection point in the trajectory of India’s welfare state. Designed to repeal and replace the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), 2005, the new legislation fundamentally alters the social contract between the state and the rural poor.1 While the government frames this transition as a modernization necessary to align rural development with the “Viksit Bharat 2047” (Developed India) vision, critics and economists view it as a structural dismantling of the rights-based framework that has defined rural social security for two decades.3

The Act introduces a statutory increase in guaranteed employment from 100 to 125 days per household 1, a move touted as an enhancement of labor rights. However, this expansion is accompanied by deep structural adjustments: a transition from a 100% centrally funded wage bill to a 60:40 Centre-State shared funding model for most states; the replacement of demand-driven “Labour Budgets” with centrally determined “Normative Allocations”; and the introduction of a mandatory 60-day seasonal pause in public works to accommodate agricultural labor demand.5

This report offers an exhaustive analysis of the VB-G RAM G legislative framework. It examines the fiscal implications for state governments, utilizing Madhya Pradesh as a primary case study to illustrate the collision between the new funding mandates and existing state-level debt crises. Furthermore, it analyzes the technological restructuring through the Viksit Bharat National Rural Infrastructure Stack, the socio-political contestation regarding the renaming of the scheme, and the broader economic implications of shifting from a demand-driven “right to work” to a supply-managed infrastructure program.

2. Legislative Genesis and Theoretical Framework

2.1 The Rationale for Repeal

The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), enacted in 2005, was the world’s largest public works program, guaranteeing 100 days of employment to any rural household willing to do unskilled manual work. For twenty years, it functioned as a critical safety net, particularly during periods of agrarian distress and the COVID-19 pandemic.7 However, the current administration has argued that the scheme suffered from structural weaknesses, primarily an insufficient focus on creating durable, productive assets. The Rural Development Minister, Shivraj Singh Chouhan, stated that the previous regime reduced the scheme to a “dig the pit and cover the pit” exercise, failing to strengthen the rural economy permanently.8

The VB-G RAM G Bill aims to pivot from this “distress relief” model to an “asset creation” model. The stated objective is to establish a modern statutory framework that not only guarantees employment but also creates durable rural infrastructure aligned with the national goal of becoming a developed nation by 2047.1 The government asserts that this new framework will enhance transparency through digital formalization, reduce distress migration by creating local economic zones, and improve agricultural productivity through water security projects.1

2.2 The Shift in Legal Entitlement

The most profound shift in the new legislation lies in the nature of the “guarantee.” Under MGNREGA, the guarantee was absolute and demand-driven; if a worker demanded work, the state was legally obliged to provide it within 15 days, with the Centre bearing the full cost of wages.

Under VB-G RAM G, while the statutory limit is raised to 125 days, the mechanism for funding this guarantee has changed. Section 4(5) of the Bill introduces “normative allocation,” where the Central Government determines the funds available for each state based on “objective parameters”.5 This signifies a move from an open-ended financial commitment to a budget-capped provision. If a state’s demand exceeds this normative allocation, the excess cost must be borne entirely by the State Government.2 Legal scholars and economists argue that capping the budget at the central level effectively dilutes the “right” to work, converting it into a discretionary scheme limited by fiscal availability.3

2.3 Thematic Verticals and the “Stack”

Unlike the broad permissible works under MGNREGA, the new Bill mandates that all projects must fall under four specific verticals, aggregated into a digital framework known as the Viksit Bharat National Rural Infrastructure Stack 5:

- Water Security: Prioritizing water-related works to improve irrigation and groundwater tables, building on the “Mission Amrit Sarovar” initiative.1

- Core Rural Infrastructure: Construction of roads and foundational connectivity to integrate villages with markets.

- Livelihood-related Infrastructure: Creation of storage facilities, processing units, and market yards to support income diversification.

- Climate Resilience: Special works designed to mitigate the impacts of extreme weather events such as floods and droughts.1

This categorization is intended to ensure that public expenditure results in tangible economic multipliers rather than temporary relief. However, this centralization of project planning—where works are aligned with national master plans like PM Gati Shakti—reduces the autonomy of the Gram Sabhas (village councils) to decide works based on local needs, a core tenet of the original MGNREGA.4

3. Fiscal Federalism: The Redistribution of Financial Burden

The VB-G RAM G Bill introduces a radical restructuring of the financial relationship between the Centre and the States regarding rural welfare. This shift has ignited a fierce debate on fiscal federalism, with opposition states arguing that the Bill penalizes them for implementing a central law.

3.1 The 60:40 Funding Formula

The financial architecture of rural employment has been overhauled. Under the previous MGNREGA regime, the Union Government paid 100% of the unskilled wage bill and 75% of the material costs. States were responsible only for 25% of material costs and unemployment allowances.2

The new Bill mandates a shared responsibility model. For the majority of states, the funding pattern is now 60:40, meaning the Centre pays 60% and the State pays 40% of the total cost (wages + materials).

Table 1: Comparative Funding Structures (MGNREGA vs. VB-G RAM G)

| Component | MGNREGA (Old) | VB-G RAM G (New) | Impact on States |

| Unskilled Wages | 100% Centre | 60% Centre / 40% State | Massive new liability; wages were previously fully funded. |

| Material Costs | 75% Centre / 25% State | 60% Centre / 40% State | Increase in state share from 25% to 40%. |

| Admin Costs | 100% Centre | 60% Centre / 40% State | New administrative burden. |

| Special Category States | 90:10 Ratio | 90:10 Ratio | Status quo maintained for NE & Himalayan states. |

| Union Territories | 100% Centre (No Legislature) | 100% Centre | No change for UTs without legislature. |

| Excess Expenditure | Borne by Centre | 100% Borne by State | Penalty for exceeding “normative allocation.” |

Source Analysis:.2

3.2 The Fiscal Impact on General Category States

The shift to a 40% contribution is not merely an adjustment; it is a fiscal shock. Estimates indicate that states will collectively have to bear approximately ₹55,000 crore of the estimated annual cost of ₹1.51 lakh crore.4 For context, under MGNREGA, states primarily managed implementation while the Centre managed the finance. Now, states must find tens of thousands of crores in their existing budgets to fund a scheme over which they have limited design control.

This creates a regressive dynamic. Poorer states like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh typically have the highest demand for rural employment due to higher poverty levels. These are also the states with the weakest fiscal capacity. By tying the implementation of the scheme to the state’s ability to pay 40% of the wages, the Bill risks suppressing work generation in the regions that need it most. As noted by the NREGA Sangharsh Morcha and global scholars, cash-strapped states may simply stop authorizing work once their state-budgeted funds run dry, effectively nullifying the 125-day guarantee.3

3.3 The “Normative” Trap

The concept of “Normative Allocation” exacerbates this fiscal pressure. In the previous demand-driven model, if a drought occurred in Rajasthan, work demand would spike, and the Centre was legally obligated to release additional funds. Under VB-G RAM G, the Centre determines a “normative” amount at the start of the year. If a drought occurs and demand spikes, the state must pay 100% of the costs exceeding that normative limit.2 This transfers the entire financial risk of climate disasters and economic downturns from the Union to the States.

Opposition leaders and finance ministers from states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu have flagged this as a direct violation of the federal spirit, arguing that the Centre is retaining the credit for the scheme (branding it “Viksit Bharat” and “Ram”) while offloading the bill to the states.4

4. Labor Market Dynamics: The Seasonal Pause and Wage Regulation

The VB-G RAM G Bill introduces mechanisms that fundamentally alter the labor market dynamics in rural India, shifting the focus from “labor protection” to “labor supply management.”

4.1 The 60-Day Mandatory Pause

Section 6 of the Bill mandates that state governments must notify a period aggregating to 60 days in a financial year, covering peak agricultural seasons (sowing and harvesting), during which no works under the Act shall be undertaken.1

Rationale: The government argues that continuous public works during farming seasons create a labor shortage for agriculture, driving up wages artificially and increasing the cost of food production. By pausing the scheme, they aim to ensure “adequate availability of agricultural labor” for farmers.1

Critique: Critics view this as a form of state-sanctioned labor control. By withdrawing the public safety net exactly when private demand peaks, the state removes the worker’s bargaining power. Without the alternative of government work, landless laborers are forced to accept whatever wages are offered by private landlords. This provision is described by activists as “stripping workers of wages, choice, and dignity,” effectively functioning as a subsidy to the land-owning class at the expense of the laboring class.6 Furthermore, this assumes that all rural workers are agricultural laborers, ignoring those who may not find farm work due to caste dynamics, disability, or mechanization.3

4.2 Wage Determination and Minimum Wages

Section 10 of the Bill empowers the Centre to specify wage rates. Crucially, the Bill retains the controversial provision (similar to Section 6(1) of MGNREGA) that delinks these rates from the Minimum Wages Act, 1948.4 This allows the government to pay wages that are often lower than the statutory minimum wage of the state.

Table 2: Disparity in Daily Wage Rates (Selected States, 2024-25)

| State | MGNREGA Wage (₹) | State Min. Wage (Agriculture) (₹) | Gap (₹) |

| Madhya Pradesh | 243 | 256 | -13 |

| Bihar | 245 | 362 | -117 |

| Haryana | 374 | 499 | -125 |

| Kerala | 346 | 868 | -522 |

| West Bengal | 250 (Approx) | 384 | -134 |

Source Data:.13

The data reveals that in many states, the central notification creates a “sub-subsistence wage floor.” By continuing this practice under VB-G RAM G, the state perpetuates a system where public employment pays less than what the state itself deems the minimum for survival. Critics argue that this violates Article 23 of the Constitution regarding forced labor.4

5. Case Study: Madhya Pradesh

Madhya Pradesh (MP) offers a critical lens through which to view the practical implications of VB-G RAM G. As a state with high poverty, significant tribal populations, and a heavy reliance on rural employment, MP stands to be disproportionately affected by the structural changes.

5.1 The Debt Crisis vs. The New Fiscal Burden

Madhya Pradesh is currently navigating a severe fiscal crisis. As of late 2025, the state’s total debt has crossed ₹4.65 lakh crore, a figure that exceeds its entire annual budget of ₹4.21 lakh crore.14 The state is borrowing approximately ₹125 crore per day merely to service existing obligations and fund populist schemes like “Ladli Behna”.14

Into this fragile fiscal environment enters the VB-G RAM G mandate. Under the new 60:40 split, MP will be required to contribute 40% of the total cost of the employment guarantee. Given that MP is a high-utilization state for MGNREGA, this 40% share represents a massive new line item in the budget.

- Scenario: If MP cannot raise this revenue, it faces a choice: cut funding for other schemes, increase borrowing (worsening the debt crisis), or—most likely—suppress the implementation of VB-G RAM G by delaying work orders to limit state liability.

- Impact: If the state limits work to manage its budget, the “125-day guarantee” becomes meaningless for the rural poor in MP, leading to increased distress migration.

5.2 Political Support and Cultural Convergence

Despite the fiscal danger, the political leadership in MP has embraced the Bill. Chief Minister Mohan Yadav has staunchly defended the legislation, particularly the renaming aspect. He has framed the opposition’s critique of the “Ram” name as an “aversion to Lord Ram,” linking the Bill to the broader cultural nationalism project.15

Furthermore, the state is actively developing the “Ram Van Gaman Path”—a tourism circuit tracing the route Lord Ram took during exile.17 CM Yadav has explicitly instructed panchayats to prioritize works linked to this path within their development plans.18 This suggests a convergence where VB-G RAM G funds might be directed toward creating infrastructure for this religious tourism circuit, fulfilling the “core rural infrastructure” and “livelihood” verticals of the new Act while serving the state’s ideological goals.

5.3 Ground-Level Perception

In Bhopal, initial reactions from potential beneficiaries have been mixed but cautiously optimistic regarding the promise of more work. Interviews suggest that laborers are primarily focused on the increase from 100 to 125 days, viewing it as a necessary income boost.19 However, these beneficiaries are largely unaware of the fiscal mechanics (the 60:40 split) that might prevent that promise from materializing. The disconnect between the legislative promise (125 days) and the fiscal reality (state inability to pay) creates a potential flashpoint for future unrest.

6. Technology and Governance: The “Stack” and Surveillance

The Bill places immense faith in technology to solve governance challenges. It mandates the creation of the Viksit Bharat National Rural Infrastructure Stack, a unified digital platform for planning, monitoring, and executing works.5

6.1 Data-Driven Governance

- Geospatial Planning: Works will be planned using satellite imagery and integrated with the PM Gati Shakti Master Plan to ensure they align with national infrastructure corridors.10

- Viksit Gram Panchayat Plans (VGPP): While the text mentions “bottom-up” planning, the aggregation of these plans at the block and district levels, and their forced alignment with the “Stack,” suggests a centralization of decision-making. If a Gram Panchayat wants a well, but the “Stack” prioritizes a road for Gati Shakti connectivity, the local demand may be overridden.21

6.2 The Digital Exclusion Risk

The Bill codifies the requirement for digital attendance and Aadhaar-based payments.1 While intended to curb corruption (ghost workers), experience with MGNREGA shows that digital barriers often lead to exclusion.

- The “Technological Fix”: The reliance on AI-based fraud detection 9 introduces a “black box” of governance where workers may be denied wages or work based on algorithmic flags they cannot challenge.

- Wage Delays: The Bill stipulates that states must pay compensation for delayed wages. However, if the delay is caused by central software glitches or fund release delays (a chronic issue under MGNREGA), the burden of compensation still falls on the state, further straining state finances.6

7. Socio-Political Contestation: The Battle for “Ram”

The renaming of the scheme from Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act to VB-G RAM G has catalyzed a profound ideological conflict.

7.1 “Ram Rajya” vs. “Hey Ram”

The acronym “RAM G” (Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission – Gramin) is not accidental. The government frames it as a step toward “Ram Rajya”—an ideal state of governance envisioned by Gandhi but centered on the figure of Lord Ram.8

- Government Narrative: Ministers argue that MGNREGA was only named after Gandhi in 2009 for electoral gains. They assert that “Ram” resonates with the rural ethos and that the scheme’s new focus on self-reliance honors Gandhi’s true vision better than the “pit-digging” of the past.15

- Opposition Narrative: The Congress and Trinamool Congress (TMC) view the removal of Gandhi’s name as an attempt to erase the legacy of the freedom struggle and secularism. They argue that invoking “Ram” in a secular employment act is a polarizing tactic designed to communalize welfare.8 Opposition MPs staged fierce protests, tearing papers and holding dharnas, calling it a “systematic murder” of the poor’s rights.23

7.2 Political Implications

The renaming serves to re-brand the most visible touchpoint of the Indian state in rural areas. By changing the name on job cards, bank transfers, and work sites, the incumbent government aims to transfer the political credit of the scheme from the Congress legacy to its own “Viksit Bharat” brand. This is crucial for retaining rural support bases, especially as the BJP seeks to expand its footprint in southern and eastern states where regional parties dominate.24

8. Comparative Analysis: MGNREGA vs. VB-G RAM G

To understand the magnitude of the change, a direct comparison of the key pillars of both Acts is essential.

| Feature | MGNREGA (2005) | VB-G RAM G (2025) | Implications of Change |

| Philosophy | Rights-Based / Demand-Driven | Supply-Managed / Normative | The “Right” is now conditional on budget availability. |

| Annual Limit | 100 Days | 125 Days | Theoretical expansion of benefit. |

| Funding (Wages) | 100% Union | 60% Union / 40% State | Regressive burden on poorer states. |

| Funding (Material) | 75% Union / 25% State | 60% Union / 40% State | Increased cost for states. |

| Work Availability | Continuous (On Demand) | Restricted (60-day Pause) | Loss of safety net during agri-seasons; labor supply control. |

| Budgeting | Open-Ended (Labour Budget) | Capped (Normative Allocation) | End of the “unlimited” guarantee. |

| Permissible Works | Broad / Gram Sabha Led | 4 Verticals / Stack Integrated | Centralization of asset planning. |

| Branding | Mahatma Gandhi | Viksit Bharat / Ram | Ideological shift from secular/freedom struggle to cultural nationalism. |

9. Critical Outlook and Conclusion

The Viksit Bharat – Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) Bill, 2025 is more than a policy tweak; it is a fundamental re-engineering of India’s rural safety net.

The Proponent’s View: The Bill modernizes a decaying system, forcing states to have “skin in the game” through financial contributions, ensuring assets are durable and mapped to national needs, and protecting the agricultural sector from wage inflation. Ideally, it creates a virtuous cycle of infrastructure creation and rural prosperity.1

The Critic’s View: The Bill dismantles the “guarantee.” By capping funds via normative allocations and offloading 40% of the cost to states—many of whom, like Madhya Pradesh, are drowning in debt—the Centre ensures that the scheme will shrink in practice. The 60-day pause is seen as a regression to feudal labor relations, stripping the poor of their only leverage against low agricultural wages.3

Future Trajectory:

The success of VB-G RAM G will largely depend on the fiscal capacity of state governments. In wealthy states, the transition may be smooth. However, in the “poverty belt” of India—states like Bihar, MP, and UP—the high state share may lead to a de facto shutdown of the program. If states cannot pay their 40%, work will stop, and the statutory guarantee of 125 days will remain a paper promise. As the legislation moves into implementation, the friction between the Centre and States over funding, and the tension between “labor rights” and “fiscal discipline,” will likely define the political economy of rural India for the next decade.

The replacement of “Gandhi” with “Ram” is symbolic of this wider shift: from a welfare state rooted in socialist, rights-based principles to a developmental state rooted in fiscal conservatism, centralized planning, and cultural nationalism.